Using the most important gravitational wave detector ever made, we have now confirmed earlier experiences that the material of the Universe is consistently vibrating. This background rumble is probably going brought on by collisions between the big black holes that reside within the hearts of galaxies.

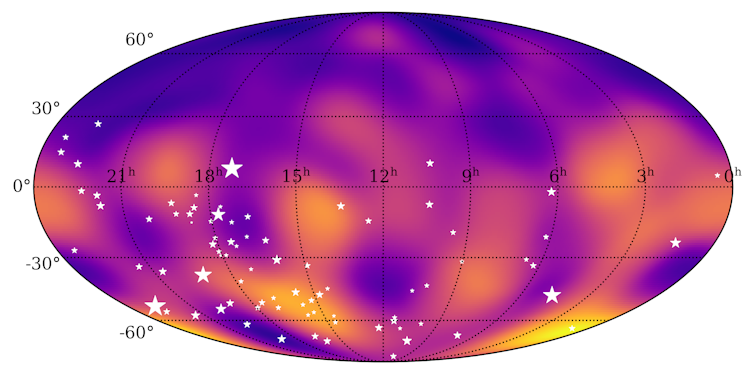

The outcomes from our detector – an array of quickly spinning neutron stars unfold throughout the galaxy – present this ‘gravitational wave background’ could also be louder than beforehand thought. We have additionally made probably the most detailed maps but of gravitational waves throughout the sky, and located an intriguing ‘sizzling spot’ of exercise within the Southern Hemisphere.

Our analysis is printed immediately in three papers within the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Ripples in house and time

Gravitational waves are ripples within the cloth of house and time. They are created when extremely dense and large objects orbit or collide with one another.

The densest and most large objects within the Universe are black holes, the remnants of lifeless stars. One of the one methods to review black holes is by looking for the gravitational waves they emit once they transfer close to one another.

Just like mild, gravitational waves are emitted in a spectrum. The most large black holes emit the slowest and strongest waves – however to review them, we’d like a detector the dimensions of our galaxy.

The high-frequency gravitational waves created by collisions between comparatively small black holes could be picked up with Earth-based detectors, and so they had been first noticed in 2015. However, proof for the existence of the slower, extra highly effective waves wasn’t discovered till final 12 months.

Several teams of astronomers world wide have assembled galactic-scale gravitational wave detectors by carefully observing the behaviour of teams of specific sorts of stars. Our experiment, the MeerKAT Pulsar Timing Array, is the most important of those galactic-scale detectors.

Today we have now introduced additional proof for low-frequency gravitational waves, however with some intriguing variations from earlier outcomes. In only a third of the time of different experiments, we have discovered a sign that hints at a extra lively universe than anticipated.

We have additionally been in a position to map the cosmic structure left behind by merging galaxies extra precisely than ever earlier than.

Black holes, galaxies and pulsars

At the centre of most galaxies, scientists consider, lives a gargantuan object often called a supermassive black gap. Despite their monumental mass – billions of occasions the mass of our Sun – these cosmic giants are tough to review.

Astronomers have recognized about supermassive black holes for many years, however solely instantly noticed one for the primary time in 2019.

When two galaxies merge, the black holes at their centres start to spiral in direction of one another. In this course of they ship out gradual, highly effective gravitational waves that give us a possibility to review them.

We do that utilizing one other group of unique cosmic objects: pulsars. These are extraordinarily dense stars made primarily of neutrons, which can be across the measurement of a metropolis however twice as heavy because the Sun.

Pulsars spin tons of of occasions a second. As they rotate, they act like lighthouses, hitting Earth with pulses of radiation from hundreds of sunshine years away. For some pulsars, we are able to predict when that pulse ought to hit us to inside nanoseconds.

Our gravitational wave detectors make use of this truth. If we observe many pulsars over the identical time frame, and we’re unsuitable about when the pulses hit us in a really particular method, we all know a gravitational wave is stretching or squeezing the house between the Earth and the pulsars.

However, as a substitute of seeing only one wave, we count on to see a cosmic ocean filled with waves criss-crossing in all instructions – the echoing ripples of all of the galactic mergers within the historical past of the universe. We name this the gravitational wave background.

A surprisingly loud sign – and an intriguing ‘sizzling spot’

To detect the gravitational wave background, we used the MeerKAT radio telescope in South Africa. MeerKAT is among the most delicate radio telescopes on this planet.

As a part of the MeerKAT Pulsar Timing Array, it has been observing a gaggle of 83 pulsars for about 5 years, exactly measuring when their pulses arrive at Earth. This led us to discover a sample related to a gravitational wave background, solely it’s kind of totally different from what different experiments have discovered.

The sample, which represents how house and time between Earth and the pulsars is modified by gravitational waves passing between them, is extra highly effective than anticipated.

This may imply there are extra supermassive black holes orbiting one another than we thought. If so, this raises extra questions – as a result of our current theories recommend there must be fewer supermassive black holes than we appear to be seeing.

The measurement of our detector, and the sensitivity of the MeerKAT telescope, means we are able to assess the background with excessive precision. This allowed us to create probably the most detailed maps of the gravitational wave background up to now. Mapping the background on this method is important for understanding the cosmic structure of our Universe.

It could even lead us to the last word supply of the gravitational wave indicators we observe. While we expect it is probably the background emerges from the interactions of those colossal black holes, it might additionally stem from modifications within the early, energetic universe following the Big Bang – or maybe much more unique occasions.

The maps we have created present an intriguing sizzling spot of gravitational wave exercise within the Southern Hemisphere sky. This type of irregularity helps the thought of a background created by supermassive black holes quite than different options.

However, making a galactic-sized detector is extremely complicated, and it is too early to say if that is real or a statistical anomaly.

To affirm our findings, we’re working to mix our new information with outcomes from different worldwide collaborations below the banner of the International Pulsar Timing Array.

Matthew Miles, Postdoctoral Researcher in Astrophysics, Swinburne University of Technology and Rowina Nathan, Astrophysicist, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation below a Creative Commons license. Read the unique article.