North Carolina Gov. Roy Cooper, on his final day in workplace Tuesday, commuted the dying sentences of 15 inmates to life in jail with out parole.

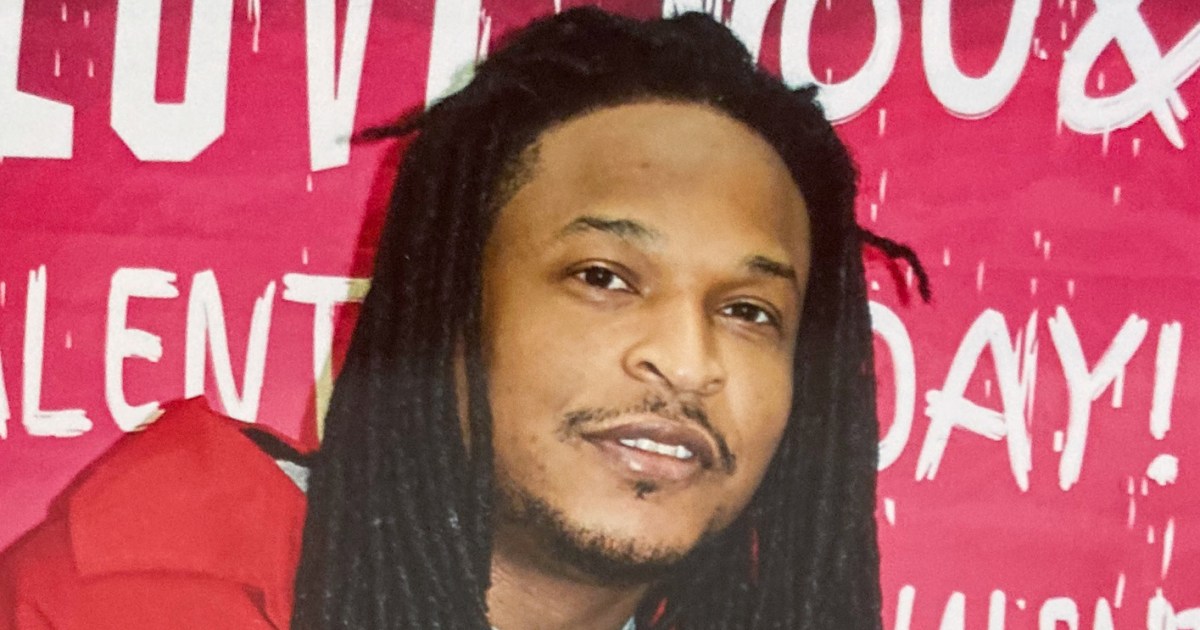

One of the prisoners receiving clemency was convicted assassin Hasson Bacote, a Black man who had challenged his sentence under the Racial Justice Act of 2009, a groundbreaking state legislation that permits condemned inmates to hunt resentencing if they will present racial bias performed a task of their circumstances.

The reprieves got here as Superior Court Judge Wayland Sermons Jr. was contemplating the case of Bacote, who was sentenced to dying in 2009 by 10 white and two Black jurors.

“These critiques are among the many most tough choices a Governor could make and the dying penalty is probably the most extreme sentence that the state can impose,” Cooper mentioned in a statement. “After thorough overview, reflection, and prayer, I concluded that the dying sentence imposed on these 15 folks needs to be commuted, whereas making certain they may spend the remainder of their lives in jail.”

While Cooper insisted that “no single issue was determinative within the choice on anybody case,” among the many elements thought of had been “potential affect of race, such because the race of the defendant and sufferer, composition of the jury pool and the ultimate jury.”

Death penalty opponents had been urging Cooper to commute the sentences of all 136 prisoners presently on dying row in North Carolina. While the Democratic governor stopped wanting that, no prisoner has been executed by the state since 2006.

Cooper’s transfer was applauded by the American Civil Liberties Union, the Legal Defense Fund, the Center for Death Penalty Litigation, and others working to overturn the dying penalty.

“This choice is a historic step in the direction of ending the dying penalty in North Carolina,” Cassandra Stubbs, director of the ACLU’s Capital Punishment Project said in a statement.

The different inmates whose sentences had been commuted are:

Iziah Barden, 67, convicted in Sampson County in 1999; Nathan Bowie, 53, convicted in Catawba County in 1993; Rayford Burke, 66, convicted in Iredell County in 1993; Elrico Fowler, 49, convicted in Mecklenburg County in 1997; Cerron Hooks, 46, convicted in Forsyth County in 2000; Guy LeGrande, 65, convicted in Stanly County in 1996; James Little, 38, convicted in Forsyth County in 2008; Robbie Locklear, 52, convicted in Robeson County in 1996; Lawrence Peterson, 55, convicted in Richmond County in 1996; William Robinson, 41, convicted in Stanly County in 2011; Christopher Roseboro, 60, convicted in Gaston County in 1997; Darrell Strickland, 66, convicted in Union County in 1995; Timothy White, 47, convicted in Forsyth County in 2000; Vincent Wooten, 52, convicted in Pitt County in 1994.

Sermons started reviewing the Bacote case in February, after the ACLU and different teams filed a problem on behalf of the condemned man from Johnston County.

Now 38, Bacote has been held in a Raleigh jail as dying sentences in North Carolina remain on hold, partly, attributable to authorized disputes and difficulties acquiring lethal injection medicine.

The legislation that Bacote used to problem his sentence was handed in 2009. But in 2013, then-Gov. Pat McCrory, a Republican, repealed the legislation, arguing that it “created a judicial loophole to keep away from the dying penalty and never a path to justice.”

But the state Supreme Court in 2020 dominated in favor of most of the inmates, permitting those that, like Bacote, had already filed challenges of their circumstances, to maneuver forward.

At the time, almost each individual on dying row, together with each Black and white prisoners, filed for critiques beneath the Racial Justice Act, according to The Associated Press.

During Bacote’s two-week trial court docket listening to, a number of historians, social scientists, statisticians and others testified that the jury choice course of in Johnston County, a majority-white suburban space close to Raleigh that prominently displayed Ku Klux Klan billboards throughout the Jim Crow period, had lengthy been contaminated by racism.

In court docket filings, Bacote’s legal professionals instructed that native prosecutors on the time of his trial had been “almost two instances extra more likely to exclude folks of shade from jury service than to exclude whites.” In Bacote’s case, prosecutors selected to strike potential Black jurors from the jury pool at greater than 3 times the speed of potential white jurors, the legal professionals argued.

Bacote’s authorized staff additionally supplied proof that indicated that in Johnston County, the dying penalty was 1 ½ instances extra more likely to be sought and imposed on a Black defendant and two instances extra possible “in circumstances with minority defendants.”

The workplace of North Carolina’s then-attorney normal, Josh Stein, had sought to delay Bacote’s listening to. They argued in a court docket submitting that the claims made by Bacote’s legal professionals had been primarily based, partly, on a Michigan State University research that the North Carolina Supreme Court had already found last year to be “unreliable and fatally flawed.”

While the AG’s workplace mentioned in its court docket submitting that racial bias in jury choice is “abhorrent,” the workplace added {that a} “declare of racial discrimination can’t be presumed primarily based on the mere assertion of a defendant; it should be proved.”

Stein, a Democrat, is now the governor-elect of North Carolina.