Editor’s Note: This article was initially revealed by The Art Newspaper, an editorial accomplice of CNN Style.

CNN

—

Lorraine O’Grady, an indefatigable conceptual artist whose work critiqued definitions of identification, died in New York on Friday aged 90. Her gallery, Mariane Ibrahim, confirmed her dying by way of e-mail, including that it was because of pure causes.

O’Grady grew to become an artist comparatively late in life, when she was in her early 40s, after which labored for an additional 20 years in relative obscurity earlier than her work began coming to widespread consideration within the early 2000s. She was included within the landmark 2007 exhibition “WACK!: Art and the Feminist Revolution” on the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles and the 2010 Whitney Biennial in New York. In 2021, the Brooklyn Museum hosted a serious retrospective, “Lorraine O’Grady: Both/And.” For the event the artist, then in her late 80s, debuted a brand new efficiency artwork persona that concerned her donning a full swimsuit of armor.

“I believed that once I had the retrospective, there can be this nice large second once I would go into the galleries and see all of my work on the similar time, in the identical place, and have this large Aha!” she advised New York Magazine in 2021. “The engagement of the viewers, which includes a back-and-forth of question-and-answer, is the factor that was lacking.”

Performance and back-and-forth questioning with an viewers are hallmarks of the three tasks O’Grady is arguably greatest identified for — two beneath her personal title, the opposite as a member of the nameless feminist collective the Guerrilla Girls. In 1980, she premiered her most well-known efficiency persona, Mlle Bourgeoise Noire, a determine clad in a costume created from 180 pairs of white gloves, throughout a gap at Just Above Midtown, a non-profit gallery championing Black artists’ work. After handing out white chrysanthemums to these in attendance, she slipped on a pair of white gloves, whipped herself with a white cat-o’-nine-tails and, earlier than leaving, shouted a poem that ended: “Black artwork should take extra dangers!!!” (She would reprise the function the next yr throughout a gap on the New Museum in New York for an exhibition that she had not been invited to indicate in, although she had been requested to take part in its schooling programming.)

Then, in 1983, she entered a float into the annual African American Day Parade in Harlem. It featured a big, gilded and empty body, and was accompanied by a troupe of 15 Black performers employed by O’Grady. Each one carried their very own body, holding them up in entrance of spectators lining the parade route, different performers and even — in a single indelible picture of O’Grady wielding her body — a New York Police Department officer. Images from that challenge, “Art Is…” entered the broader lexicon of visible tradition as O’Grady’s profession gained momentum in latest a long time. In late 2020, a video launched by the Biden-Harris marketing campaign celebrating its election victory reinterpreted the piece, with O’Grady’s blessing.

The little one of Jamaican immigrants, O’Grady was born in Boston on September 21, 1934. Her identification was formed each by her Caribbean heritage and her household’s anomalous class place. Her dad and mom had been upper- and middle-class in Jamaica, however have been confined to working-class jobs after they moved to the US. She didn’t match naturally with both the predominantly White working-class neighborhood in Boston’s Back Bay, the place she spent most of her childhood, or with Boston’s upper-middle-class African American elite.

“I at all times felt that no one knew my story, but when there wasn’t room for my story, then it wasn’t my downside,” she advised New York Magazine. “It was theirs.”

Before discovering artwork, O’Grady tried many pursuits and careers, first opting to review Spanish literature at Wellesley College earlier than altering tracks to review economics. After graduating she briefly labored for the Department of Labor earlier than changing into a fiction author. She enrolled within the Iowa Writers’ Workshop on the University of Iowa, however by no means completed her research there. She moved to Chicago and labored for a translation company earlier than beginning her personal, finishing tasks for purchasers together with Encyclopedia Britannica and Playboy. In the early Seventies she moved to New York City and have become a rock music critic, writing for The Village Voice and Rolling Stone.

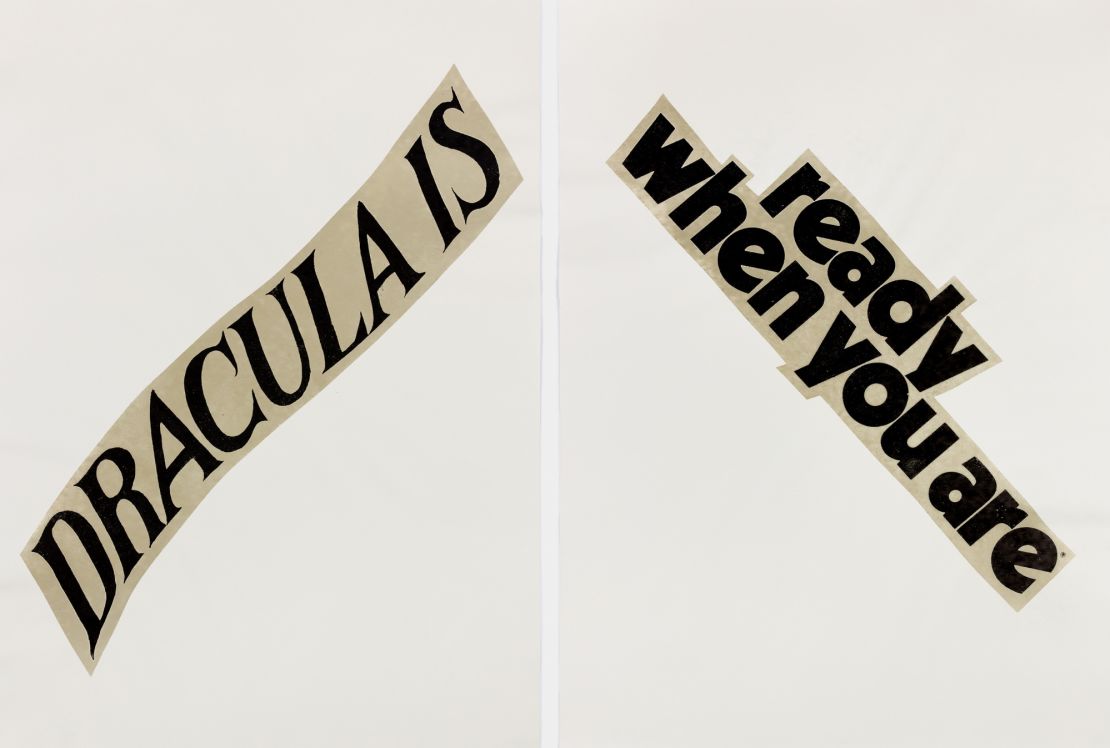

In the mid-Seventies she began educating literature on the School of Visual Art in New York. While reducing up an version of The New York Times to make a present, she started collaging collectively fragments of texts. These collages would grow to be her first collection, “Cutting Out the New York Times.”

“The downside I at all times had was that irrespective of who I used to be with or what I did, I received bored fairly rapidly,” O’Grady advised New York Magazine. “This was one thing I knew I might by no means get tired of, as a result of how can I get bored? I might at all times be studying, and I might by no means, ever grasp it. That was a part of the enchantment.”

After that, although she continued to write down — a ebook of her collected writings, edited by the scholar and critic Aruna D’Souza, was revealed by Duke University Press in 2020 — art-making grew to become O’Grady’s major exercise. She additionally taught new generations of artists, taking over a full-time job on the University of California, Irvine, within the early 2000s.

“I don’t assume the common one that turns into an artist begins off considering of it as something apart from self-expression,” O’Grady advised the Brooklyn Rail in 2016. “That will get educated out of them regularly. ‘Self-expression’ is one thing that will get tamped down in graduate faculty particularly — educating at UC Irvine, I watched folks struggling towards that, towards having to learn to match into the market. I don’t know that the character of artwork itself has modified; I do assume the concept of an ‘artwork profession’ has modified.”

Defying the standard concepts of an artwork profession till the top, O’Grady had been busier than ever lately. Last yr she left her longtime supplier Alexander Gray to affix Mariane Ibrahim, a Chicago-based gallery with areas in Mexico City and Paris. At the time of her dying, she was engaged on her first solo present with the gallery, at its French house, scheduled for spring 2025.

“Lorraine O’Grady was a drive to be reckoned with,” Ibrahim mentioned in an announcement. “Lorraine refused to be labeled or restricted, embracing the multiplicity of historical past that mirrored her identification and life’s journey. Lorraine paved a path for artists and ladies artists of colour, to forge vital and assured pathways between artwork and types of writing.”

This previous April, O’Grady received a prestigious Guggenheim Fellowship, which was to help a brand new efficiency artwork piece reviving an outdated character from her previous work. And whereas the reception for her artwork modified drastically over time, the work itself maintained an mental rigor, criticality and playfulness that spanned her performances, collages, photographic diptychs and collection, writings and extra.

“I’m old style. I believe artwork’s first aim is to remind us that we’re human, no matter that’s,” she advised the Brooklyn Rail. “I suppose the politics in my artwork could possibly be to remind us that we’re all human. Art doesn’t change that a lot, truly. I’ve learn a lot of poetry from Ancient Egypt and Ancient Rome they usually speak about the identical issues poets do at the moment. Is anybody extra down and soiled and on the similar time extra introspective than Catullus?”

Read extra tales from The Art Newspaper right here.