Astronomers have found a hefty new Super-Earth that is as dense as lead. This rocky world may simply be the leftover core of a gasoline big that flew too near its solar.

Meet K2-360 b, an exoplanet that packs 7.7 Earths-worth of mass right into a ball that is simply 1.6 occasions the dimensions of our house world. That shakes out to a density of about 11 grams per cubic centimeter, on par with that of lead.

That makes it the densest identified planet in its class – ultra-short-period (USP) Super-Earths. Granted, that is a really particular class, besides, K2-360 b nonetheless ranks among the many densest of all identified exoplanets.

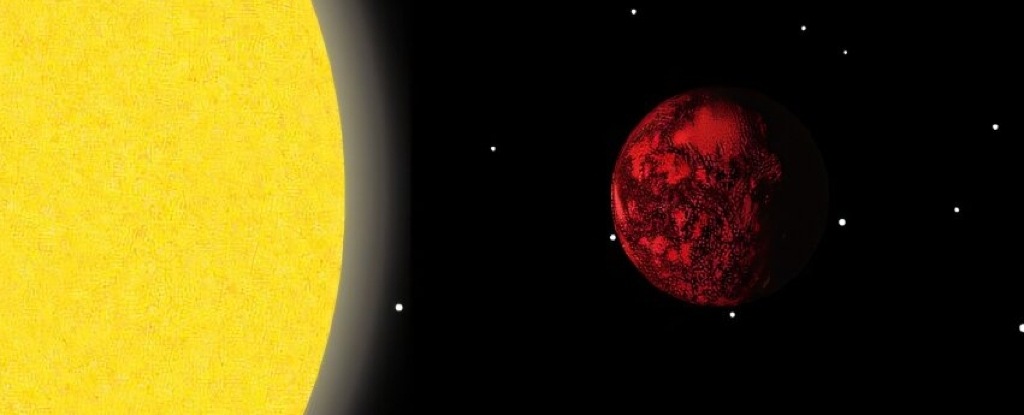

A planet’s interval is what we would generally name its yr: how lengthy it takes to orbit its host star. K2-360 b earns its “extremely quick” moniker with a yr that is shorter than an Earth day, simply 21 hours.

Being cuddled up so near the star not solely helped astronomers discover it, however it additionally offers some clues about the way it got here to be so dense within the first place.

K2-360 b was found in 2016, when the planet’s shadow was noticed passing in entrance of its star by NASA’s K2 mission. Follow-up observations have now allowed astronomers to measure its mass and radius, which they might then use to calculate its density.

This Super-Earth’s lead-like density places it in a really unique membership. It’s twice Earth’s density of 5.5 grams per cubic centimeter, and nonetheless thicker than different high-density worlds like GJ 367b and TOI-1853b.

The absolute unit TOI-4603b has it beat, at a whopping 14.1 grams per cubic centimeter, however that one is correct on the cusp of what may even be referred to as an exoplanet – it is perhaps higher described as a brown dwarf or ‘failed star.’

At the alternative finish of the size sit exoplanets within the Kepler 51 system, with densities of simply 0.03 grams per cubic centimeter. For reference, that is roughly the density of cotton sweet.

To work out what makes K2-360 b so strong, the staff created a mannequin of the Super-Earth’s inside, primarily based on observations of it and its host star. From this, plainly the planet most likely has an enormous iron core that accounts for round 48 % of its mass.

So how does such a cannonball of a planet even kind? The researchers counsel that it could truly be the lifeless core of a world that was as soon as a lot bigger and resided farther away from the star. Over time it migrated inwards, the place the extreme radiation stripped away the gasses of its ambiance, leaving a strong hunk of rock that is possible coated in oceans of lava.

Clues to this situation have been discovered within the wobble of the host star. It seems that K2-360 b isn’t alone within the system – lurking farther out is a a lot bigger planet, K2-360 c, with a measurement and density possible just like that of Neptune.

“Our dynamical fashions point out that K2-360 c might have pushed the internal planet into its present tight orbit by a course of referred to as high-eccentricity migration,” says Niels Bohr Institute astrophysicist Alessandro Trani.

“This entails gravitational interactions that first make the internal planet’s orbit very elliptical, earlier than tidal forces progressively circularize it near the star. Alternatively, tidal circularization might have been induced by the spin-axial tilt of the planet.”

The research is simply additional proof that the Universe is awful with unusual planets that pulp sci-fi writers might solely dream of.

The analysis was printed within the journal Scientific Reports.